Permaculture

There are many definitions of permaculture, varying among sources and over time. A recent one which stays close to the original concept describes permaculture as an integrated set of central ethics and design principles for agricultural practices that reflect the holistic dynamics of ecosystems.[1] By carefully observing these ecosystem dynamics, permaculture principles “teach us how to design ways of living that have the stability and resiliency of natural systems”.[2] As such, permaculture design mimics the patterns, the diversity and the dynamics of these natural systems to create agricultural and other commoning practices that are self-sustaining, energy-efficient and respectful of all living beings and their interrelationships.

While permaculture places a strong emphasis on organic farming and food production, this is by no means the end of the story. Among others, permaculture offers design patterns for:

- restoring soils, protecting biodiversity and using water wisely.

- building resilient local economies around careful management of natural resources.

- creating solidarity and communities that enable people to enjoy meaningful lives and engage in actions that support each other and the planet.

Overall, it's an approach that integrates natural resources, social relationships and culture through ethics of care for the earth, care for people and fair share.

Overview

The concept of permaculture — originally a contraction of the words permanent, culture and agriculture — was first introduced in the 1970s by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren. Working in Tasmania, their joint efforts to develop a set of principles and tools for applied agriculture science were inspired by Howard Odum's work on ecosystem ecology, Masanobu Fukuoka's work on natural farming (shizen nōhō), Yeamoan's keyline design and Ruth Stout and Esther Deans' no-dig gardening.[3] They also drew on Tasmanian Aboriginal knowledge on protection of the land as well as on other earth care practices.

Over the years, through workshops and interdisciplinary fieldwork, the initial approach to permaculture has evolved into an integrated design system for sustainable living, with an emphasis on systems thinking and the conscious design of ecological landscapes, including people, buildings and organisations.[4] Through its development, there has been increased attention toward cooperation and mutual responsibility to support life and enhance beneficial interrelationships between species.[5] Nowadays, permaculture functions both as a social movement, with a set of principles applicable to all decision-making, and as a means of activism on how to create earth life systems that are not only resilient and sustainable over time, but also creative and regenerative.

Elements

Permaculture based agriculture is practiced in both rural and urban locations, on large areas as well as on small plots of land and in backyard gardens. Many people have taken and are taking permaculture design courses, there is a lot of information on dedicated websites and permaculture sites have been set up in almost every region of the world (see More Resources section below).

Permaculture can help build synergistic systems that sustain and restore life. There's a growing movement of people following this path, through training, sharing information and experimentation. Many cooperatives and networks have taken on permaculture principles and postures to apply them to their specific areas of life (social, economic, political, cultural, digital).[6]

Permaculture is all about observing ecosystems, identifying direction and design based on natural patterns, flow and change. Through this lens, ecosystems are envisioned as complex networks where humans collaborate with other life forms to produce harmonious and sustainable energy systems.

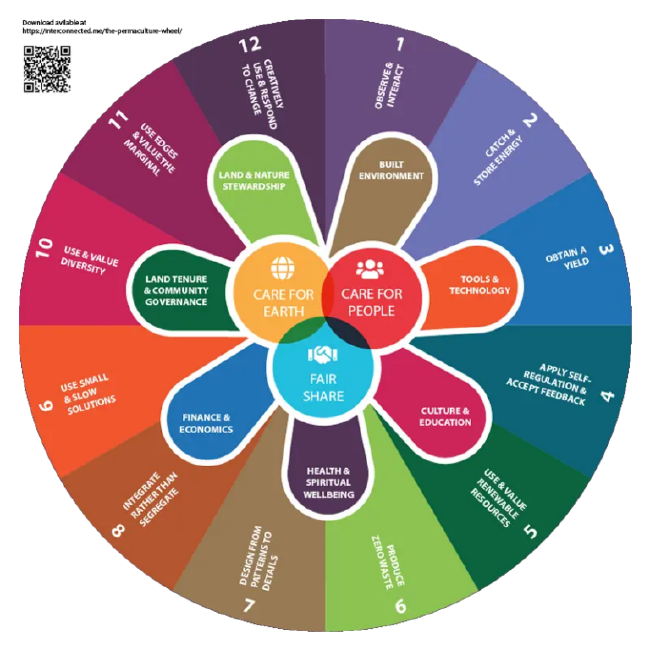

To create energy flow and surplus energy without doing damage, permaculture design builds on 3 core ethics: care for the earth, care for people and fair share (also known as future share):

- Care for the earth includes restoring and nurturing soil, forests, water and air.

- Care for people recognizes the importance of social justice and human solidarity in fostering oneself, one’s kin and one’s community.

- Fair share combines ecological and social justice by producing and consuming within ecosystems limits, redistributing surpluses to those in need, and modifying lifestyles to be sustainable and regenerative.

These three central ethics are joined by twelve design principles:

| № | Principle | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Observe and interact | Take time to observe, rely on skills in observation and sensitive interaction to find the best path forward. Avoid absolute truths/values |

| 2 | Catch and store energy | Learn how to save and restore energy that we are depleting or wasting, for the next generations to come |

| 3 | Obtain a yield | Design systems that provide for self-reliance at all levels, including the personal. Create positive feedback loops |

| 4 | Apply self-regulation, accept feedback | Develop behaviour and culture that is attuned to the feedback signals from nature to prevent overexploitation |

| 5 | Use and value renewable resources and services | Make best use of renewable natural resources, harmonise with life and minimise consumptive demands |

| 6 | Produce no waste | Waste not, want not. Apply the 6R’s: reduce, reuse, recycle, refuse, rethink, repair |

| 7 | Design from patterns to details | Integrate observed patterns in design of zones and structures. Make subsystems for organisation and planning |

| 8 | Integrate rather than segregate | Develop awareness of the importance of relationships, how they work together to support each other in the design of self-reliant systems, and act accordingly |

| 9 | Use small and slow solutions | Cultivate patience and a balanced view to counter the attraction of fast-moving processes and large-scale systems |

| 10 | Use and value diversity | Value natural and cultural diversity, aim to conserve them, and actively commit to doing so |

| 11 | Use edges and value the marginal | Make use of catchment, keylines, guilds, symbiotic relationships and other ‘edges’’ where life interacts and thrives[7] |

| 12 | Creatively use and respond to change | Integrate change in a deliberate and cooperative way and respond or adapt to large-scale system change beyond our control or influence |

Perspectives on Permaculture

People involved in permaculture become more closely attuned to the rhythms of natural systems and the subtle indicators of these system’s health or endangerment. (Bollier and Helfrich, 2019).

Permaculture offers useful insights into agroforestry, polyculture, organic agriculture and integrated water management. It opens up new perspectives on human social support for life, can broaden understanding of adaptive management and regenerative practices and can contribute to the agroecological transition. (Krebs and Bach, 2018).

Both rural and urban permaculture can be an effective tool for raising awareness.

Cities notably, can offer great learning and educational opportunities on sustainability and climate resilience. (URBact, 2023)

Permaculture as a concept is decolonial by nature, but the movement, which is made up of people largely from the dominant culture, is not.

Diversity enriches us, makes us more resilient and allows for new kinds of collaboration. We need such diversity in the permaculture movement.

Let’s elevate marginalised voices and invite the unnoticed ones. Also, let’s honour and name the indigenous cultures around the world that have inspired permaculture and give reparation where needed to those whose land we occupy. (Santa Cruz Permaculture, 2021).

Permaculture is about cultivating a culture of sharing, caring and mutual responsibility. It is about fostering community that aligns with the core ethics of earth care, people care and fair share. But how fair is fair share? Who decides what is fair? Is there equality? Equity? What about the privileged and the exploited? How to participate when (re)productive life-work takes up most of the time and energy? How to strike a balance? (Flores, 2018).

In a context of important needs and limited resources, stress and exhaustion are recurrent. How can we ensure that organisations and cooperatives engaged in social and solidarity economy support people and their decision-making in a way that stimulates and revitalizes them? Permaculture could provide some answers to this question, as it places care for earth and people at the heart of its ethos and pays attention to slowing down, communing and the creation of meaning. (Michaud and Pinard-L'Abbée, 2024)

Through cooperation, mutual responsibility and interweaving of relations at the local level, permaculture moves away from centralised models of production and consumption that require massive inputs of energy, institutions and technology and that result in the destruction of resources. As such, permaculture provides an alternative way to create natural and human capital, to move energy through positive feedback loops and to store energy through catchment in the form of water, living soil, sun, solidarity, trust, etc. (Paraphrased from Blais, 2006).

More Resources

Films

- Permaculture minidocs playlist, by Happen Films

- Permacuture Explained in 6 Minutes by Huw Richards

- The Permaculture Principles, Oregon State University Ecampus

- What is Permaculture? (And Why Should I care?) by Our Changing Climate

- Permaculture's Origin by Geoff Lawton

- Kiss the Ground, a film by Big Picture Ranch and The Climate Studio

- Five Seasons, a film by Thomas Piper

Articles

- Indigenous Domain: Pilgrims, Permaculture and Perl, Joline Blais

- Green City Diaries: Fab Lab and the language of nature, Matthew Piper

- The 12 Design Principles of Permaculture, David Holmgren

- Permaculture Principles Extended, Never Ending Food

- A Comprehensive Guide to David Holmgren’s Permaculture Design Principles, Deep Green Permaculture

- The Shared Patterns of Indigenous Culture, Permaculture and Digital Commons, David Bollier

- What Permaculture can Teach us about Commons, David Bollier

- On Permaculture, Entitlement, and That Pesky Third Ethic: All Aboard the Elephant in the Room, Heather Jo Flores

- Decolonizing Permaculture, Santa Cruz Permaculture Team

Websites

- International Permaculture Collaboration Laboratory

- Permaculture Global

- Permaculture Commons

- The Permaculture Signal

- Permaculture Principles

- Stories on Permaculture and Ecofeminism

- Permies (Permaculture and Homesteading Goofballs)

- PermacultureLibrary (French)

Books and Publications

- Birnbaum, Juliana, and Louis Fox, eds. Sustainable [r]Evolution: Permaculture in Ecovillages, Urban Farms, and Communities Worldwide. Sustainability / Permaculture. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 2014.

- Bollier, David, and Silke Helfrich. Free, Fair, and Alive: The Insurgent Power of the Commons. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers, 2019.

- Hemenway, Toby. The Permaculture City: Regenerative Design for Urban, Suburban, and Town Resilience. 1st ed. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2015.

- Holmgren, David. ‘Essence of Permaculture’, 2013. https://holmgren.com.au/downloads/Essence_of_Pc_EN.pdf.

- ———. Permaculture One: A Perennial Agriculture for Human Settlements. Hepburn Springs: Melliodora Publishing, 1978.

- ———. Permaculture: Principles & Pathways beyond Sustainability. Revised edition. Hepburn, Victoria, Australia: Melliodora Publishing, 2017.

- Leahy, Terry. The Politics of Permaculture. FireWorks 5. London: Pluto press, 2021.

- Lockyer, Joshua, and James R. Veteto, eds. Environmental Anthropology Engaging Ecotopia: Bioregionalism, Permaculture, and Ecovillages. First paperback edition. Studies in Environmental Anthropology and Ethnobiology, volume 17. New York Oxford: Berghahn, 2015.

- Macnamara, Looby, and Rebecca Storch. People & Permaculture: Caring and Designing for Ourselves, Each Other and the Planet. East Meon, Hampshire: Permanent Publ, 2012.

- Mollison, B. C. Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual. Tyalgum, Australia: Tagari Publications, 1988.

Research

- Ferguson, Rafter Sass, and Sarah Taylor Lovell. ‘Permaculture for Agroecology: Design, Movement, Practice, and Worldview. A Review’. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 34, no. 2 (April 2014): 251–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-013-0181-6.

- Gasperoni, Chiara, and Kylyan Marc Bisquert i Pérez. ‘Pour En Lire plus : Notre Ville Permaculturelle.’ Éducation Relative à l’environnement Volume 18-1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.4000/ere.9521. (French)

- Hathaway, Mark and Center for Environmental Philosophy, The University of North Texas. ‘The Practical Wisdom of Permaculture: An Anthropoharmonic Phronesis for Moving toward an Ecological Epoch’. Environmental Ethics 37, no. 4 (2015): 445–63. https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics201537442.

- Krebs, Julius, and Sonja Bach. ‘Permaculture—Scientific Evidence of Principles for the Agroecological Design of Farming Systems’. Sustainability 10, no. 9 (8 September 2018): 3218. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093218.

- Michaud, Valérie, and Mylène Pinard-L’Abbée. ‘Prendre Soin et Apprendre à Dire Non : Les Apports de La Permaculture Pour Repenser La Participation Aux Décisions En Économie Sociale et Solidaire’. Ad Machina, no. 8 (13 December 2024): 251–76. https://doi.org/10.1522/radm.no8.1849. (French)

- Roux-Rosier, Anahid, Ricardo Azambuja, and Gazi Islam. ‘Alternative Visions: Permaculture as Imaginaries of the Anthropocene’. Organization 25, no. 4 (July 2018): 550–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508418778647.

Image Credits

- Lead Image by Vincent Erhart

- Permaculture Design Principles Wheel sourced from Never Ending Food

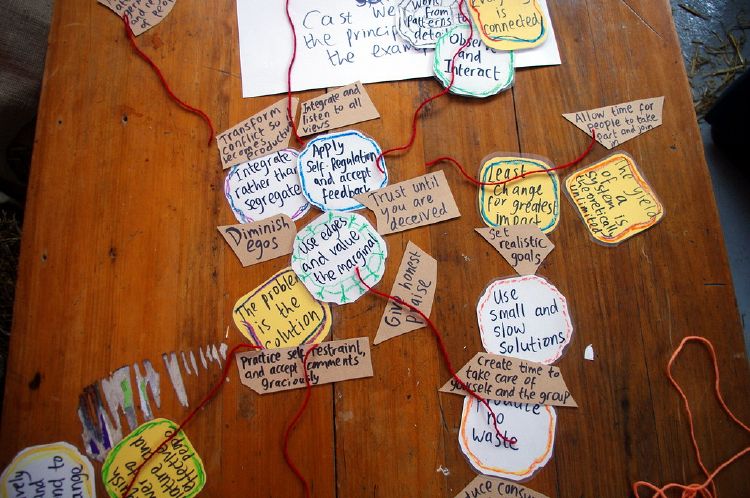

- Yorkshire Permaculture Brainstorming by Permaculture Association

Footnotes

- ↑ Free, Fair, and Alive: The Insurgent Power of the Commons. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers, 2019.

- ↑ Permaculture: A Designer's Manual. Tyalgum, Australia: Tagari Publications, 1988.

- ↑ For more resources on these influences we recommend the following books:

- Natural Farming: Fukuoka, Masanobu. Shizen nōhō wara ippon no kakumei. Shinpan. Tōkyō: Shunjūsha, 2004.

- Keyline Design: Yeomans, P. A. Water for Every Farm: Yeomans Keyline Plan: Sustainable Agriculture Creates Living Soil to Adsorb Salt and CO2. Edited by Ken B. Yeomans. 2008 edition. Australia Fair Southport, Queensland: Keyline Designs, 2008.

- No-Dig Gardening: Stout, Ruth. Gardening without Work: For the Aging, the Busy and the Indolent. Blodgett, OR: Norton Creek Press, 2011; Deans, Esther. No-Dig Gardening ; Leaves of Life. Pymble, N.S.W.: HarperCollins, 2001.

- ↑ Holmgren, David. ‘Essence of Permaculture’, 2013.

- ↑ Hathaway, Mark and Center for Environmental Philosophy, The University of North Texas. ‘The Practical Wisdom of Permaculture: An Anthropoharmonic Phronesis for Moving toward an Ecological Epoch’. Environmental Ethics 37, no. 4 (2015): 445–63.

- ↑ Some examples worldwide include the Black Permaculture Network, the Philippine Permaculture Association, Ghana's Permaculture Women Empowerment Project and the PermaQueer crew.

- ↑ Some definitions for these terms:

- Catchment is a system for accumulating a critical mass of a needed resource, like water or soil or minerals, in order to trigger self-organizing system, i.e., life forms, that then spread over the landscape. Some natural examples of catchment include the sun, plant, carbohydrates, bodies of water, geothermal energy, and plate tectonics.” Joline Blais, “Indigenous Domain: Pilgrim, Permaculture and Perl",

- A keyline is a specific topographic feature related to the natural flow of water on a tract of land. It is used in keyline design as a landscaping technique to optimize beneficial use of the water resources.

- A guild is a mutually beneficial group of species (insects, plants) that works in harmony and contributes to the larger ecosystem.

- Symbiosis is an association between two or more species of organisms that is permanent or long lasting, and that can be beneficial, not affecting or harmful to the organisms involved. It is common in nature at all levels - between fungi and algae, between bacteria and plants, etc. For more perspectives on Symbiosis see Margulis, Lynn. Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution. Science Masters. New York: Basic Books, 1998 and Paracer, Surindar, Vernon Ahmadjian, and Vernon Ahmadjian. Symbiosis: An Introduction to Biological Associations. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000)